As South Africa winds up the ‘Youth Month’, ‘Men’s Health Month’, and the world using the same month to raise global awareness about drug abuse and illicit drug trafficking, it is important to make a reflection of the historical relationship the African youth, African males and women have with the substance of which scholars in the health discipline regard as a gateway drug – this due to alcohol being a psychoactive substance. A substance said to alter the manner the brain responds to emotions and stimuli.

Historically, in rural South Africa alcohol had multiple purposes in the African society. According to BM Setlalentoa et al (The social aspects of alcohol misuse/abuse in South Africa), alcohol was not just limited to a means of payment and the strengthening social relations, but associated with masculinity, and also the perceived strengthening of the anatomy.

African communities, not limited to those on the most southern tip of the continent, alcohol was used in the celebration of special and key occasions such as marriages and success in harvest.

Consumption was in moderation and subject to strict customary guidelines as to when you may consume, how much you may consume, why and who may consume.

Those were strict regulations, and enforcement thereof. Alcohol was mainly for domestic consumption.

The “tot” or “dop” system, being traced from around the 1650’s is said to have come with the arrival of Dutch settlers in the Cape.

This was a practice of which farm workers were partially renumerated with alcohol for their hard labour, instead of solely with money or other less destructive means – the system meant a routine issuing of wine to largely ‘male’ farm workers at regular intervals during a working day.

This destructive system, common in what is now called the Western Cape, created widespread and uncontrollable alcohol abuse and dependency, among mainly male farm workers and within families.

This to date contributes to serious social ills and perpetuates harmful stereotypes against certain demographics. It was only formally outlawed in 1960, with enforcement strengthening in the 1990s, however its legacy continues to impact communities to date.

A study conducted by the National Library of Medicine argues that despite the official and legislative prohibition of the tot – system in the 60’s to 90’s, it persists in farms.

Even though it is a minority of farms that currently actively practice the dop system, the ramifications of the historical institutionalisation of massive alcohol consumption are widespread.

Multitude of farm workers in South Africa continue to live and work under adverse conditions that created under the legacy of apartheid policies, which enables the persistence.

The European farmers and traders involuntary influenced a move by Africans to drink European liquor, which certain scholars called “Cape Smoke”, moving the native from the commonly known sorghum beer, consumed before the British, Dutch or French came to their shores.

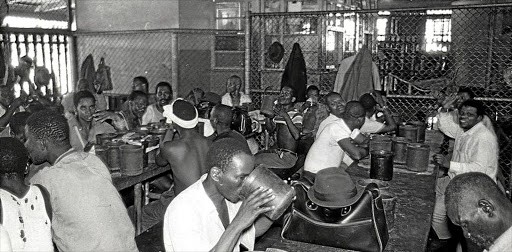

The “Durban system” – A system developed in the early twentieth century and legalised in Durban; would be later adopted at national level by the regime.

The Durban system was a state protected (municipal) monopoly over alcohol production, distribution and consumption of which revenue generated from these municipal ‘beer halls’ was “invested” to administer Africans in largely urban areas – Africans were unfortunately and unknowingly funding their segregation, while simultaneously alcohol destroyed their families and communities.

With the national legislation of beer halls around the early 1900’s, and its emphasis that it was wrong for the natives to own, operate, and profit from their own beer halls, rose the rapid proliferation of illegal “shebeens”, ultimately resulting in unmonitored and uncontrolled drinking patterns and abuse.

It is argued that the prohibition forced Africans to seek out and find creative ways of acquiring more of both home-brewed and Cape Smoke kind of liquor.

These are significant factors that led to the abuse of alcohol – people consumed more because there was no guarantee that they would get a drink again.

The illegal operations around alcohol had economic spin-offs for mainly women as they sold it as means of supplementing the meagre wages their husbands were earning.

With supply shortages, need to meet demand, people experimented with various methods of brewing, which were easier and quicker, often compromising quality and the health of the consumer.

Setlalentoa BMP et al also argued that alcohol was used by colonisers as an instrument to seize power – a form of political, economic and socio-cultural domination, micro-level practices that went ignored by the societal leaders and the natives of the time.

The “dop” system, prevalent in the Western Cape, managed to perpetuate racial stereotypes and inferences that the problem of over-drinking is biologically determined and not socially constructed in certain racial groups.

According to the DTIC – SA alcohol demand patterns, South Africa has the 5th highest consumer rate of alcohol in the world. The average drinker takes in an average of 30 litres of alcohol per year.

31% of consumers are said to be aged 15 and above, also noting that, the average age for starting to consume alcohol is around 13-14 years for both genders. 59% of drinkers are heavy or binge drinkers. 26% of alcohol is homemade or illegally produced.

43% of adult men drink booze as compared to the one in five female consumers, with African households spending 3.8% of their total expenditure on alcoholic beverages, compared to 3.0% by Coloured households and 1.5% by White households.

Tracking the history of alcohol in the African community provides clarity on behaviours we witness today.

A youth believing they are consuming alcohol while alcohol consumes them; men who seek refuge in booze; and the continued destruction of our families, communities and future thanks to the substance that we have been socialised for centuries to love, while it consumers our very existence and has us defocused on things that really matter, just like our forebears. Written by Bongani K Mahlangu, a B Com Economics, B Com Honours Economics and Master of Commerce in Economics graduate from the North – West University. Has worked in Banking, Competition Commission of SA, public sector and in advisory. Often serves as a political economic analyst and commentator on radio and television networks

Written by: Lindiwe Mabena

Similar posts

Current show

Upcoming shows

Sunday Feels Part II, With Karen

10:00 am - 2:00 pm

The Global Experience with Just Mo

2:00 pm - 6:00 pm

Sundaze with Fif_Laaa

6:00 pm - 10:00 pm

Savage Nights with Thabo X and Shamiso

10:00 pm - 12:00 am

Playground

12:00 am - 5:00 am

Latest posts

COPYRIGHT 2023