OPINION | Preservation of white privilege is the killer of the nation’s dream to be free

The year 2025 marks the 49th anniversary of June 16, 1976. It is almost half a century of memory with which we are dealing. By this dialogue we are engaging in a struggle against forgetting.

Locally: June 16 was the bravest action – 16 years after the Sharpeville Massacre of March 21, 1960.

Internationally: It took 16 years of debating in the United Nations to adopt a resolution declaring apartheid a crime against humanity. The convention was adopted in November 1973. The convention only took effect July 18, 1976. This was exactly a month after June 16, 1976.

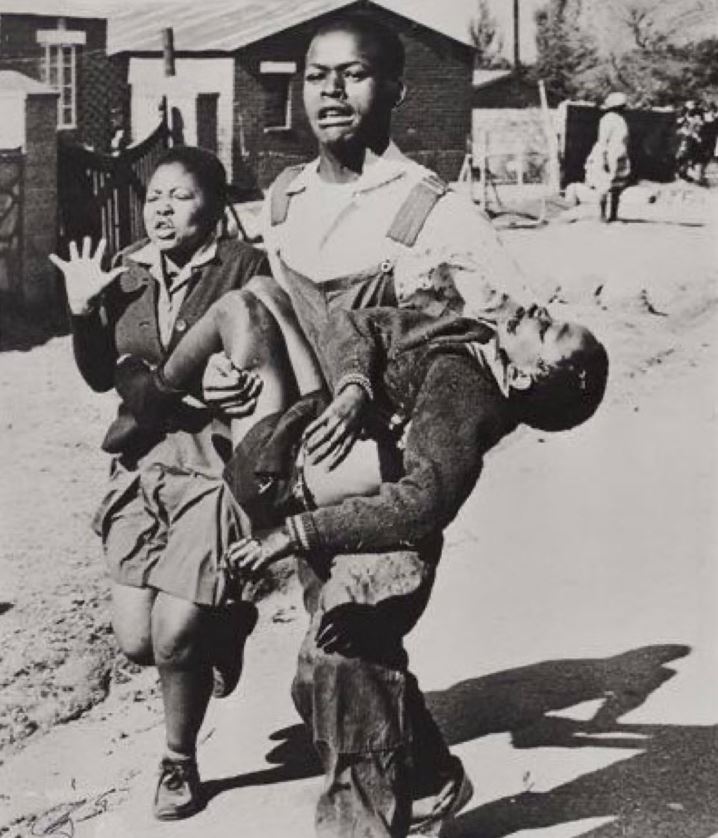

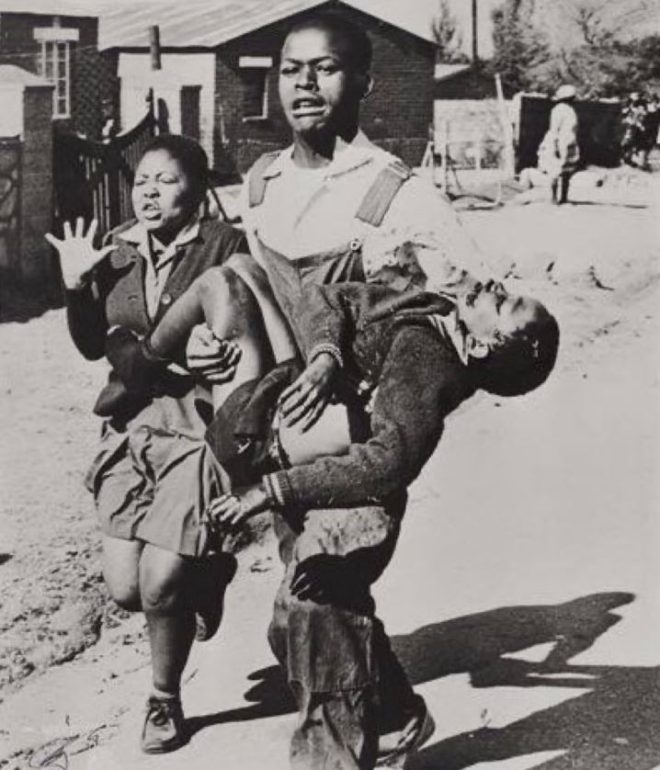

Media wise: Many remember the photographer Sam Nzima who took the picture. Few know that when the police pursued Nzima for the camera, it was Tom Khosa, a driver at the time, who had already rescued the film, rushed to the newsroom to deliver it to the editors who decided on that picture to be published in the newspaper the next day. The World would not have known what happened.

Journalists, Sophie Tema and Sam Nzima, did not only cover the story, but also went an extra mile to rush fatally wounded Hector Pietersen to Phomolong Clinic to get medical attention. In other words, they did their duty as journalists and at the same time performed human duty to help Hector Pietersen receive medical attention. That element of human compassion is rare. In the heat of the action, journalists rush for the story to be printed.

A picture of a vulture waiting for a Sudanese child to die, to act as good, taken by award-winning photographer, Kevin Carter, in 1973 presented a different journalistic mindset of performance of duty to Tema and Nzima.

Humanity has long been on the ropes. But no matter how vicious the blows pounding on black bodies have been, black people have not given up giving humanity a fighting chance.

That compassion act on the collective part of Nzima, Tema and Khosa is important to know in the lead up to the picture now symbolising epochal June 16, 1976.

From the unfailing collective presence of mind of Nzima, Tema and Khosa, lies our inspiration to use our creativity and cultural expression to preserve and share the deeper, more complex histories for our young.

What should be appreciated under conditions of oppression and tyrannical governments, is the habitual delight to see long queues to voting booths in the electoral road to fame for political office but seldom listen to the will of the people after the attainment of power. Freedom of expression is the carrot that never fails to dangle and a stick forever quick to follow. Freedom of expression is not automatic. It is not a given. It is fought for.

Nzima, Tema and Khosa demonstrated their share of fighting in this direction. A bouquet of flowers is not a picture of what tyrants present to people riding up against dehumanising harm inflicted upon them.

Idi Amin was notorious for stating: “There is freedom of expression, but I cannot guarantee freedom after speech.”

Talking truth to power is not a smooth sailing mission. This is not only limited to the government. It extends to churches, companies, business, education, medical, academic, sports, cultural and social settings.

What makes history a bit complex is the refusal to see that in the eyes of the oppressors all else is game to bring down whatever is deemed a threat. To oppressors there is no child, woman, or man to dispose of threats, perceived or real, standing in the path of its rule.

Believability of this phenomenon becomes more complex when assumed liberators act no better than oppressors. Oppression is heartless. It is soulless. Given that, it is foolish to expect mindfulness from it.

Unleashing live ammunition to protesting school children is consistent with the initial cruelty driven to madness that nothing else matters to retention of its rule.

Hector Pietersen was 13 when shot. The system did not care that he was part of the protesters. The system only saw a threat. The immediate action the system took was to deter (discourage) the rest by opening fire, which claimed the life of Hector. Hector was a symbol. It did not start and end with him. There were many more.

Today’s youth carry forward the spirit of 1976, not only through protest, but through innovation, hustle, and cultural leadership. The songs they write, poetry they render, art they produce, graphic designs, messages they formulate on T-shirts, films they produce are artistic expressions reflecting the times they are in. The choice to make is to make art for perpetuation of their humiliation of their community or for its upliftment.

Dialogues in remembrance of June 16 fall in the line of upliftment to carry forward its spirit.

Sisters Thandiswa and Ntsiki Mazwai carry that spirit in their different ways. Through reading, writing, poetry, music, painting, graffiti and reflecting the realities they find themselves in – the spirit lives.

Simphiwe Dana (musician), Cyril Manganyi (artist), Palesa Mazamisa (playwriter), Sipho Mabuse (musician) are moving parts of that spirit. By music, fashion, storytelling, enterprises and play young people imagine new futures for themselves and their communities. But all these endeavours are not exempted from suppression and criminalisation.

Oppression is not known to give roses to the oppressed people for resisting it in any shape, form or age. It muzzles. It isolates. It starves. It kills. It detains. It sends people into exile. It assassinates leaders. It sends people into jail.

Oppression does that to separate leaders and followers; to break the solidarity and unity of the oppressed. To divide, rule and conquer. To silence dissenting voices is stock and trademark of its business.

One of the ways oppression maintains itself is to kill memory; make you forget; encourage you not to remember. In your forgetfulness, you are separated from those that came before you. A chain of values that lifts society to nobler heights is broken. In forgetting, you lose what the quest for true humanity entails all.

Remembering is to bring together the various parts of the same experiences of the living and the dead to refocus on the mission of all that is best to pursue to be human again, reclaim dignity and live a life that is full in conditions that affirm your humanity.

To this end, all possible must be done to make space and ways for youth-led, community-rooted solutions that honour the past while directly addressing social challenges that demand no less than economic repentance.

Since every generation tended to blame the one that came before, the June 16 generation broke with that tradition. It recognised that the generation before it had done all it could. It decided to take matters into its own hands. But since these were students, this generation took the struggle from the classroom to the streets.

Taking a leaf from that defining moment there are examples galore for the youth to follow and adopt leadership qualities to lead. The youth must be armed with tools of analysis to understand the problems affecting their communities. They should permanently ask what the recurring problems that they find themselves in and develop a deeper working understanding of the causes.

The youth must understand that they are total beings, politically, economically, spiritually, culturally, spiritually, aesthetically, epistemologically.

Economically, for example, the youth should understand that their exclusion is not by accident but by design and derives from inequality.

They are excluded in the same way that their parents were excluded. Racism has been the deciding factor.

What is missed the most about the year 1976 is that these were children of “nobodies”. Their parents were people with no instant name recognition as Mr and Mrs so and so. Their parents only became known by the actions that these children took.

With the benefit of legacy foundations and community-driven initiatives, conscious institutions should be better positioned to lend a lifting hand to youth-driven storytelling and historical reclamation. The marking of cultural icon Molefe Pheto’s 90th birthday by the artistic community falls into that cultural reclamation line.

In the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund (NMCF), for instance, what was emphasised was not the person behind the establishment of the foundation but the cause to be championed. As a result, the key message was – it is work we do that matters more than the person behind the legacy foundation.

In other words, it was living and working for something higher than us and built to last beyond our lifetimes as well as that of the NMCF founder, Nelson Mandela.

In simpler terms, live a life that tells a story of a noble cause greater than yourself, to believe in, and whose historical significance, will claim pride of place in living memory long after you are gone. The reclamation aspect anchors itself the dictum that nothing should happen for us without us. The phrase in Zimbabwe was “Nothing About Us, Without Us.”

Attention should as much be directed to media’s role today in shaping or distorting public memory around events like June 16.

The media’s glaring recollection failure is inability to show that what June 16 1976 was about had gone beyond the language issue. The issues were steeped in the totality of the black conditions afflicting the oppressed black majority and located right in the centre of the national liberation struggle for its resurrection.

This resolve was evident in the slogan Forward Ever, Backward Never. Even God had come in the picture to face the question: Senzeni Na? The question being raised was: ‘Are we not part of your creation?’ Is the colour of our skin the source of our sins that these afflictions had elected black bodies?

These questions point to the media’s convenient avoidance of the fact that South Africa is in the throes of the unfinished business of the liberation project.

Point is, black people were not only dying for freedom, but white people were also killing for oppression. The dying and the killing is occasioned by continuation of white privilege and constitute a major obstacle to achieving true freedom. South Africa is not a picture of what liberation had promised.

The media lacks the courage to tell the full story of what June 16, 1976, students’ nationwide uprisings were about.

To recapture the whole picture about June 16, 1976, the job is cut out for young creatives, who want to merge historical consciousness with economically viable storytelling or enterprise.

Nothing better positions anyone to provide a responsive solution than a clear articulation of the problems for which one is expected to resolve in a manner that delivers the struggling majority from oppressive subordination.

It all boils down to what the statement of the problem is. Avoidance of addressing the fundamental causes to the problem leads to half-baked solutions, papering over cracks, cosmetic changes, denial of historical facts, promotion of co-optive solutions in the form of the current political power relations made to believe it is possible to function without economic power.

The storytelling arising out of such discrepancy leads to the kind of enterprises that look at black efforts through the lens preoccupied with preservation of white privilege. Written by Corporate Strategist, writer and freelance journalist, Oupa Ngwenya.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the content belong to the author and not Y, its affiliates, or employees.

Written by: Lindiwe Mabena

Similar posts

Current show

Upcoming shows

Sunday Feels Part II, With Karen

10:00 am - 2:00 pm

The Global Experience with Just Mo

2:00 pm - 6:00 pm

Sundaze with Fif_Laaa

6:00 pm - 10:00 pm

Savage Nights with Thabo X and Shamiso

10:00 pm - 12:00 am

Playground

12:00 am - 5:00 am

Latest posts

COPYRIGHT 2023